- Start Date

- Duration

- Format

- Language

- 25 nov 2025

- 12 days

- Class

- Italian

Sviluppare la mentalità del progetto e acquisire le metodologie fondamentali per impostarli e gestirli e per guidare il team di progetto verso il risultato atteso.

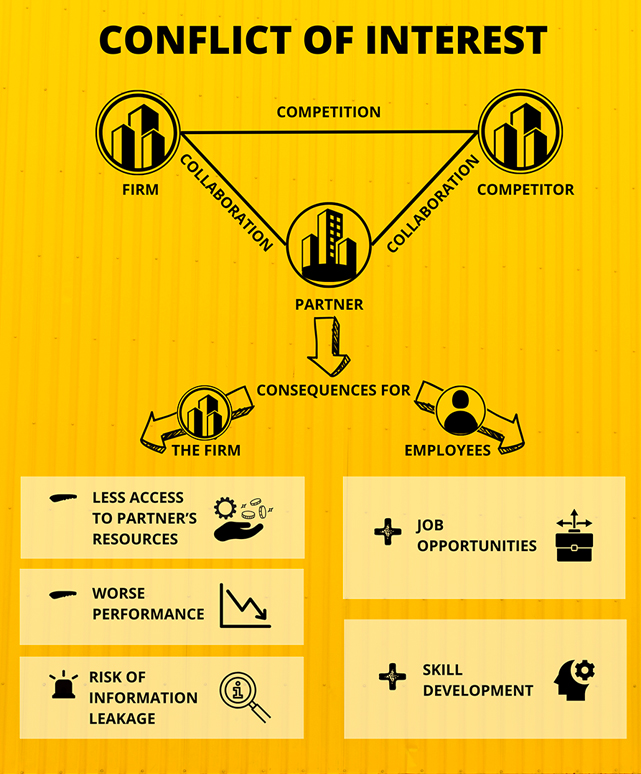

Peer competition among firms collaborating with the same partner brings about negative outcomes for several reasons. First, a firm may find it difficult to access the shared partner’s resources, especially when competing with superior peer firms. What’s more, since the shared partner’s attention is limited, the more peer firms there are, the less attention each one will get.

In addition, there’s a risk of harmful information leakage. Granting the shared partner access to proprietary information is necessary for firms to get feedback. And while they may control how much information they share, they can’t control leakage to the peer firms they’re indirectly connected with. More fundamentally, peer firms are structurally equivalent, as they vie for the partner's resources and potentially for the same consumers. In this situation, fierce competition and conflict are particularly likely to arise.

Why, then, do competitors continue to share corporate partners?

When we started to investigate this question, we conducted several interviews with employees in the video game industry where developers, who conceive and develop games, collaborate with publishers, who finance and market the games. We were surprised to learn that employees were well aware of peer competition but were not bothered by it. In fact, employees often spoke enthusiastically about their peers. That’s why we decided to examine a seemingly counterintuitive hypothesis: peer competition may hurt the company but may benefit employees.

To test this hypothesis, we built a comprehensive dataset that included detailed information on video games, the employees involved in their development, the developers they work for, and the publishers. MobyGames, a large video game documentation project, allowed us to track employees' entire careers in both public and private firms around the globe.

In this way, we were able to measure the effect of peer competition on both revenue-based performance of video games (28,560 to be exact), and on the personal success of the developers (measured by the performance of the video games they helped develop over the following year).

We found that collaboration with a shared partner gives employees the chance to overcome time, distance, and social obstacles to connect with a potential employer. Such interactions

also provide employees with coverage for forming otherwise frowned-upon relationships. For example, employees may claim to be on LinkedIn for their work, and that may be true, but they’re also making themselves known to headhunters and alternative employers.

We proposed two reasons why connections that employees develop with their counterparts in peer firms can be beneficial on a personal level: job opportunities and skill development. When an employer and potential employee already know on another, there is a greater likelihood of a match, and that match will probably be higher quality. In the meantime, the social connections formed with employees at other firms can help focal employees develop their skills. This flexibility in employee career development may not be a bad thing for managers either, if we think about the flow of talent between firms. And finally, a better match between firm and employee can be beneficial to firm performance in the long run.

Henning Piezunka, Thorsten Grohsjean. “Collaborations That Hurt Firm Performance but Help Employees’ Careers.” In Strategic Management Journal, online before inclusion in an issue. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3447.